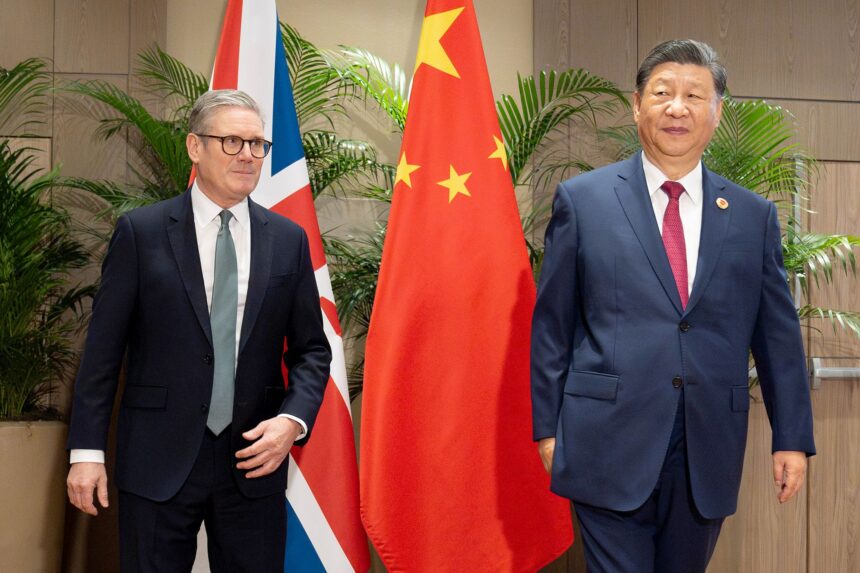

In late January 2026, the latest escalation in U.S. trade rhetoric was not merely another episode in a familiar cycle of tensions. Rather, it signalled a deeper shift in how the United States is managing its relationships with its closest allies. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s visit to Beijing—and the economic agreements and trade facilitation measures that accompanied it—highlighted a reality that can no longer be ignored: the Western world is no longer a unified bloc in its approach to China, but rather a constellation of diverging interests attempting to reposition themselves within a rapidly transforming international order.

Donald Trump’s response brought this divergence sharply into focus. While his warning to London remained largely political in tone, his message to Canada was unmistakably punitive. The threat to impose sweeping 100% tariffs on Canadian goods should Ottawa proceed with any economic rapprochement with Beijing went far beyond a conventional trade dispute. It amounted to an attempt to redraw the boundaries of what is permissible—and impermissible—within the Western alliance itself.

This posture cannot be understood outside the logic underpinning the “America First” doctrine. Within this framework, international relations are not measured by the depth of alliances but by immediate calculations of gain and loss. China, in Trump’s view, is not simply a rising economic competitor; it represents a structural threat to American dominance—across technological leadership, control of global supply chains, and even the rules governing international trade. From this perspective, any Western engagement with Beijing becomes a strategic vulnerability rather than a sovereign policy choice.

Yet this logic, however internally consistent it may appear, collides with a far more complex and less controllable global reality. Post-Brexit Britain faces economic pressures that make disengagement from the world’s second-largest economy an increasingly costly option. Canada, despite its deep and longstanding reliance on the U.S. market, has come to recognise that total dependence on a single partner in an era defined by volatility and uncertainty carries strategic risks no less serious than limited engagement with China. In this context, economic diversification ceases to be an act of disloyalty and instead becomes a mechanism for survival.

Notably, neither London nor Ottawa has sought direct confrontation with Washington or an overt crossing of red lines. Official rhetoric in both capitals has emphasised that opening channels with China does not imply a strategic realignment or abandonment of the U.S. partnership. Nevertheless, the American response suggests that even a narrow margin for manoeuvre is no longer tolerated. Herein lies the core of the crisis: when alliances shift from being partnerships rooted in mutual interests to arrangements defined by constant loyalty tests, erosion begins from within.

This erosion does not remain confined to the transatlantic sphere. The Middle East, long accustomed to navigating shifting power balances, is watching these developments with characteristic pragmatism. Growing U.S. pressure on its Western allies sends mixed signals to the region’s states. On the one hand, the United States remains an indispensable security partner; on the other, its policies appear increasingly unpredictable and more willing to weaponise economic tools for political ends. Within this relative vacuum, China finds expanding space to deepen its regional presence—through investment, technology partnerships, and even diplomatic roles once dominated by Washington.

The real danger lies not in the proliferation of partnerships or the diversification of alliances, but in the drift towards rigid polarisation. A full-scale U.S.–China trade war would not merely reshape relations between the two powers; it would disrupt global supply chains, fuel inflation, and trigger volatility in energy and food markets—costs borne disproportionately by middle-income and developing economies rather than by the major powers themselves.

Ultimately, this escalation produces no clear winners. The United States may extract short-term tactical concessions, but at the risk of undermining the trust that has sustained its alliances for decades. Its allies, meanwhile, gain greater economic flexibility, but at an uncertain political and security cost. Between these poles, a multipolar international system continues to take shape—one governed less by absolute loyalties than by delicate balances and complex calculations.

Perhaps the central lesson of this moment is that the era of unilateral dictates is receding. Managing a multipolar world cannot be achieved through tariff threats alone, but requires a more agile diplomacy—one capable of accommodating contradiction rather than suppressing it. In such a world, the defining question is no longer who we stand with, but rather: how do we move forward without being forced into a zero-sum alignment trap?

Dr. Marwa El-Shinawy – Academic and writer