The Horn of Africa saw one of the worst droughts in recent history from 2020 to 2023, worsened by La Niña, with failed rains leaving Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia in deep crisis. Families went hungry, livestock died, crops failed, and what was left was washed away by flash floods in 2023–2024 as the skies cleared. Climate change is hitting very hard where resources are scarce. The Global South is already experiencing the future that many people fear, from heatwaves in Africa’s Sahel to rising sea levels in SIDS. However, pledges made by countries are not fulfilled when it comes to funding, resilience, and adaptation.

The injustice of climate change is clearly visible in the Global South, where those who have contributed the least are suffering the most. For instance, Africa is consistently one of the regions most impacted by climate extremes, despite contributing less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions. While floods and storms have destroyed essential infrastructure, rising temperatures, unpredictable rainfall, and severe droughts have disrupted agriculture, endangering livelihoods and food production. Widespread food and water insecurity, declining health, forced migration, and displacement across vulnerable communities are all being caused by these environmental shocks. The effects of this climate injustice extend beyond the environment to include significant economic, social, and ethical ramifications for pastoralists in the Horn of Africa as well as coastal populations in the Pacific, South Asia, and Latin America.

Climate Finance: A Broken Promise

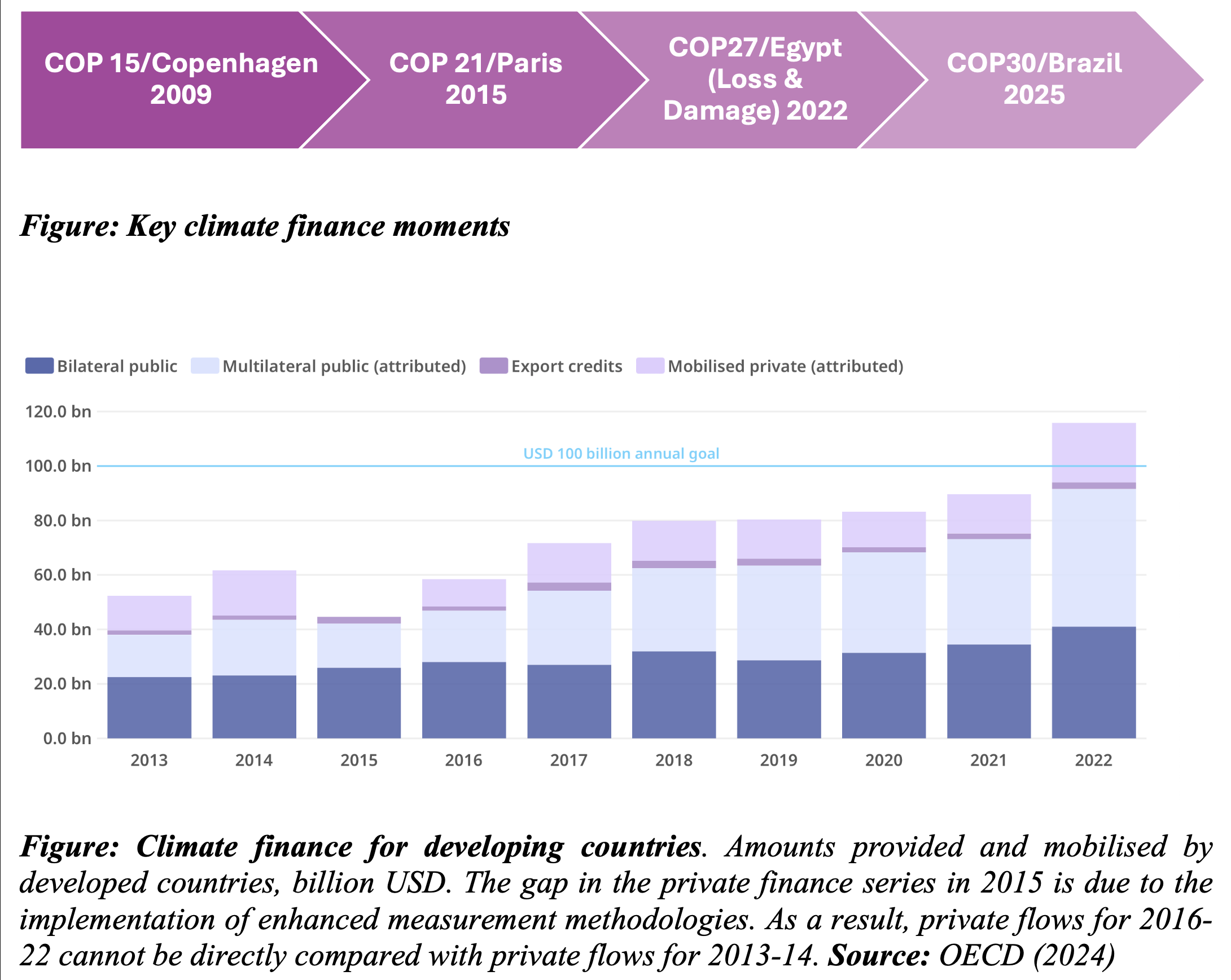

In 2009, developed countries pledged to mobilize $100 billion per year by 2020 to support climate action in developing nations – a promise meant to help the most vulnerable countries adapt and respond to a crisis they did not create. However, this objective was only accomplished two years later, in 2022. US $115.9 billion was ultimately delivered, according to the OECD’s 2024 report, but the truth is more nuanced. About 80% of this climate funding comes from public sources, frequently in the form of loans rather than grants, further burdening already fragile economies with debt. The majority of this financing is not new or increased help, but rather repurposed development aid. Even worse, only 20–30% of these funds are allocated to adaptation, which is vital for communities dealing with health risks, failed crops, and increasing sea levels. The lion’s share continues to support mitigation, which, while important, does little for those already bearing the brunt of climate shocks. Furthermore, assistance for Loss and Damage- the most pressing need for many nations in the Global South – is hardly enough. Many believe that this failed pledge is a sign of a more serious dilemma in climate diplomacy including global equity and trust.

Loss and Damage refer to the irreversible harm caused by climate change – things that can’t be prevented or changed to. This includes disappearing coastlines, lost homes and farms, dried-up water sources, and even the collapse of entire livelihoods. At COP27, held in Egypt, world leaders made a historic move by agreeing to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to support the most vulnerable countries. For many in the Global South and Africa, this was long-overdue recognition of their sufferings. But more than a year later, the fund remains largely empty, and details about how much money will be delivered, when, and by whom, are still unclear. As we look ahead to COP30 in Brazil, there’s growing pressure on wealthy nations to move beyond symbolic support and deliver real financial reparations. The upcoming Africa Climate Summit will also be critical – offering African voices a unified platform to demand justice, funding, and accountability.

The Global South does not ask for charity – it demands justice. We are losing more than just money with each season of drought, flood, or famine; we are losing lives, cultures, and futures. The climate clock is running out. It is time for citizens everywhere to hold their leaders responsible and for developed nations to transition from promises to payments. Climate finance must be need-based, equitable, and free from red tape and loan restrictions. However, accountability doesn’t end there. The Global South must unite as well, strengthening South-South collaboration, exchanging expertise, and constructing robust systems from the ground up. Because in this climate fight, solidarity is survival.

Dr. Suchismita Pattanaik, Senior Research and Policy Specialist – Physical and Environmental Science, Organisation of Southern Cooperation [All views expressed are personal]