In the heart of Cairo, where the bustle of modern life collides with the grandeur of antiquity, Egypt’s museums stand as enduring witnesses to history. They are not simply halls of stone and glass, but living spaces where the past whispers to the present. Each month, these cultural institutions highlight selected treasures—objects that are more than mere relics, but storytellers that speak to human values shared across time.

For September 2025, Egypt’s museums have chosen their “Pieces of the Month” around three deeply human themes: agriculture as the foundation of life, peace as the ultimate aspiration of civilization, and cleanliness as the essence of both spiritual and physical purity. These objects, fashioned from stone, wood, or metal, are ambassadors of meaning. They embody the wisdom of the ancient Egyptians, the farmer’s resilience, the peacemaker’s vision, and the enduring love of purity.

Farmers’ Day: The Land Tells Its Story

On 9 September, Egypt celebrates Farmers’ Day, honouring the hands that cultivate the land and feed the nation. The story of the Egyptian farmer is as old as civilization itself, beginning when the ancients first understood the secret of the Nile, harnessed its waters, and transformed its fertile soil into fields of prosperity. Museums across Egypt this month mark the occasion with artefacts that speak of this eternal bond between land and people.

At the National Police Museum in the Citadel, an unexpected treasure awaits: a marble zela’a, a jar once used to store grains. Though simple in design, it symbolises foresight and resilience, the wisdom of storing for future generations, and the philosophy of sustainability born from intimate knowledge of the life cycle.

The Gayer-Anderson Museum displays a photographic image of a farmer with authentic Egyptian features. More than a portrait, it is an artistic tableau that conveys struggle, patience, and an organic connection to the land. The farmer’s eyes capture centuries of labour, endurance, and quiet dignity.

In Bulaq, the Royal Carriages Museum presents a bronze medal from the Royal Agricultural Society, attributed to Prince Yousef Kamal. Beyond its artistry, the medal reflects the recognition of agriculture as the backbone of national power, linking rulers and farmers in the shared project of development.

At the Prince Mohamed Ali Palace Museum in Manial, a wooden statue of a farmer carrying a basket and an axe greets visitors. The axe symbolises toil, the basket the fruits of harvest. Together, they embody simplicity, perseverance, and the values of honest work.

Even the divine found ways to honour the farmer. In Helwan’s Farouk’s Corner Museum, a model of the “Harvest Goddess” reminds us that agriculture was not just an economic activity but a sacred process infused with spirituality.

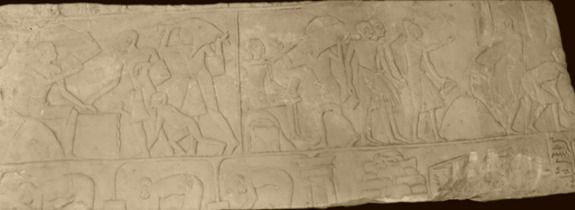

Across Egypt, more treasures echo this narrative. The Ismailia Museum exhibits basalt grindstones from the Roman era, showing continuity in agricultural practices. The Tel Basta Museum in Zagazig displays a model bronze axe, symbolising the simple tools that laid the foundations of civilization. At the Kafr El Sheikh Museum, a New Kingdom stone block carved with scenes of grain storage illustrates food security as a central concern of the state. The Suez National Museum presents an agricultural axe from Middle Egypt, a reminder of the farmer’s daily struggle.

In Alexandria’s Graeco-Roman Museum, a Ptolemaic statue of a farmer carrying a basket of fruit alongside a goat reflects a blend of Egyptian and Greek traditions, portraying the farmer as both worker and companion of nature. In Hurghada, a mural depicts female farmers carrying vegetables and wheat, testifying to women’s indispensable role in cultivation.

The Mallawi Museum in Minya houses a wooden model of three women grinding grain, dating to the First Intermediate Period. It embodies the communal spirit and cooperation essential to society. Finally, the Mummification Museum in Luxor presents a representation of Osiris, the god of agriculture and fertility, affirming that the land was always sacred at the heart of Egyptian belief.

International Day of Peace: The Legacy of Ramses II

On 21 September, the world observes the International Day of Peace. For Egypt, peace was not a passive state but an active principle of civilization. The most enduring testament to this value is the first written peace treaty in human history, signed by Ramses II and the Hittites after the Battle of Kadesh.

Egypt’s museums honour this legacy with powerful representations. In the Matrouh National Museum, a pink granite bust of Ramses II shows a calm yet resolute face, embodying the leader who sought peace after victory. At the Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, a seated statue of Ramses II bears the inscription “King of War and Peace,” capturing the balance between might and wisdom. In Aswan’s Nubian Museum, a sandstone statue from the Temple of Gerf Hussein adds to the story, reaffirming that peace was a value carved not only into stone but into the identity of the civilization itself.

World Hygiene Day: Purity of Body and Soul

The same date, 21 September, also marks World Hygiene Day. For ancient Egyptians, cleanliness was not just a routine but a ritual, tied inseparably to religion and morality. Physical purity was seen as a pathway to spiritual clarity.

At the Museum of Islamic Art in Bab El-Khalk, a steel mirror dating from the 12th–14th centuries reflects not only faces but also the high craftsmanship of Islamic civilization, affirming the shared value of personal care. The Coptic Museum in Old Cairo displays a wooden comb decorated with Byzantine ornaments, showing the intersection of cultures through daily life objects.

The Cairo Airport Museum – Building 2 exhibits a silver-decorated ewer and basin for ablution from the 19th century, reminders of the continuity of purification rituals. In Building 3, a slate palette shaped like a gazelle from the Naqada II culture illustrates how even prehistoric Egyptians linked adornment with spirituality.

The Tanta National Museum houses ivory kohl sticks, testifying to the role of eye adornment in hygiene, health, and beauty. At the Alexandria National Museum, a crystal and silver carafe from the modern era evokes the elegance of personal care in royal circles. The Royal Jewelry Museum in Alexandria displays a golden handle for grooming tools, proving that even objects of hygiene could be fashioned from luxury. At the Sohag National Museum, a copper ewer for bathing and ablution, simple in design, underscores hygiene as a universal human need.

A Dialogue Between Past and Present

The September museum pieces are more than curated displays. They form a dialogue across centuries, inviting reflection on values that remain essential today: the patience of the farmer, the wisdom of peace, and the love of purity. They reveal that Egyptian civilization was never limited to monumental architecture or military might, but was above all a profoundly human civilization that valued work, reconciliation, and spiritual cleanliness.

Through these initiatives, museums cease to be mere repositories of artefacts. They become bridges between generations, reminding Egyptians and the world alike that today’s values are not modern inventions, but inheritances from an ancient civilization whose lessons still resonate. The present, they remind us, is the natural outcome of the past.