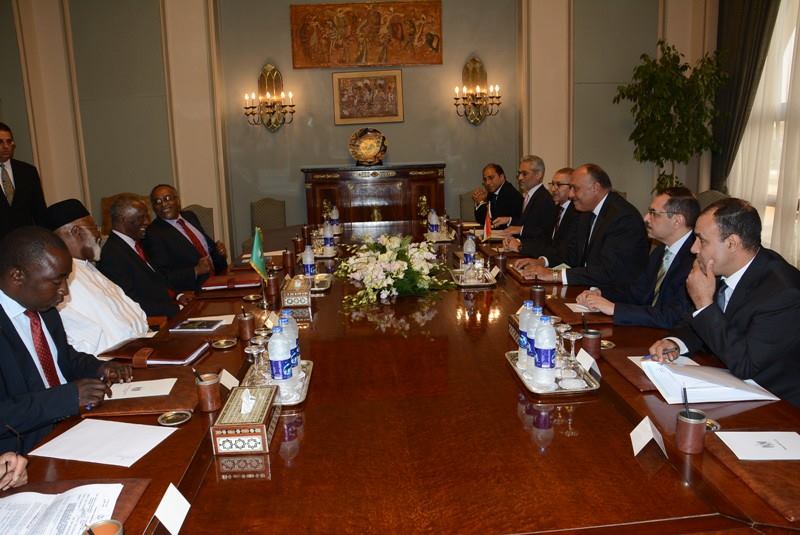

(AFP Photo / Khaled Desouki)

“If Hosni Mubarak wants to avoid a popular revolt like the one that recently took place in Tunisia he must put an end to emergency law, dissolve the fraudulent parliament and call for new free and fair elections, amend the constitution to allow for free and fair presidential elections and finally sack his current government and form a new, patriotic one that meets the demands of the Egyptian people.”

These were the five points articulated on behalf of the Muslim Brotherhood on 17 January 2011, by none other than the man who would eventually replace Mubarak. Mohamed Morsy said nothing about Mubarak stepping down however, and did not specify that his son and heir apparent Gamal should not run in the next elections.

At the time a member of the Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau, as well as the group’s official spokesperson, Morsy framed these demands as the safeguard to Egypt’s stability. He did warn of a revolution if the demands were not met, although he quoted Brotherhood founder Hassan El-Banna by saying it “would not be of our making,” but that “we will not be able to stop it,” he told Ikhwan Online.

Two days later the Brotherhood released a statement echoing Morsy’s comments and adding five more demands relating to economic and foreign policy, as well as the release of political prisoners. Again the rhetoric was that the regime needed to meet these demands so that it can avoid “a revolution that will not be of the Brotherhood’s making.”

By that time calls for nationwide protests on Police Day, 25 January, had been made on the We Are All Khaled Said Facebook page, in an attempt to replicate the recent Tunisian revolution that toppled Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Several political parties and groups announced they would join.

“The Muslim Brotherhood will not participate in the planned 25 January protests. The Brotherhood’s work is organised and it has a clear [policy] regarding calls for protests made online or calls that are made by non-organised individuals, which is not to participate,” said then Guidance Bureau member Essam El-Erian on 20 January.

Thousands took to the streets on 25 January and although some Muslim Brotherhood youth participated as individuals the group had no official representation on the street. They released a statement the next day declaring support for the protests and demanding the release of political prisoners such as Deputy Supreme Guide Khairat El-Shater and influential Brotherhood businessman Hussein Malek.

Morsy told the BBC that day that the Brotherhood would join the protests until “the people’s demands were met” and that they would take to the streets in the “Day of Rage” scheduled for 28 January. Yet again he did not mention Mubarak stepping down and despite not being part of the original demands of We Are All Khaled Said, this was repeatedly demanded by protesters on the streets. On 27 January the Brotherhood released another statement ahead of the, demanding constitutional amendments and parliamentary elections.

Following the security vacuum that resulted from the police’s withdrawal on 28 January, the Brotherhood released a statement two days later condemning the looting that took place in some areas and called on Egyptians to keep factories, bakeries and other essential services running. The country was effectively in a state of civil disobedience at the time but the Brotherhood warned that “work must resume in Egypt” and called on citizens to resume their jobs so that “things do not get out of hand and so that normality can be restored.”

(AFP Photo)

The statement stuck to the demands regarding the constitution and parliament, with Mubarak’s resignation once again absent, despite the fact that many people had been killed at the hands of the regime by that point. Another statement the next day condemned the formation of Ahmed Shafiq’s government and hailed the military’s stance while still refraining from discussing Mubarak.

Finally, on 1 February, Muslim Brotherhood Supreme Guide Mohamed Badie released a statement in which he said Mubarak had lost all legitimacy and added the president’s resignation to their other demands.

On 4 February, two days after the Battle of the Camel when Mubarak supporters stormed Tahrir Square killing several protesters and injuring dozens more, the Brotherhood released a statement again calling on Mubarak to resign. The group said it would participate in “national dialogue” as long as it was serious and contained no threats, in response to the call for dialogue made by the then-newly appointed Vice President Omar Suleiman.

The Brotherhood did participate in the meeting with Suleiman on 6 February and was represented by Morsy. The government agreed to put an end to emergency law “when the security situation improves,” and constitutional amendments were to be drafted by a committee of independent judges and politicians, prosecuting corrupt officials and allowing for more media freedoms.

Suleiman was adamant that the demand to remove Mubarak was impossible; the Brotherhood released a statement saying they disagreed and would stick to that demand. They did not pull out of the dialogue however and said they would continue to participate. The next day they denied signing an agreement published by the government and purported to be part of the national dialogue.

Finally, in their final statement during the uprising, the Brotherhood said on 9 February that it had withdrawn from the national dialogue and that it would not field a candidate for the presidency, rejecting allegations that it was behind the revolution and saying it was merely one of many participating groups. It rejected Mubarak’s formation of a constitutional amendment committee, calling for his removal.

It took the Brotherhood until February to demand Mubarak’s removal despite the youth chanting for it from day one, and other politicians demanding it from at least 27 January. After the events of 28 January the Brotherhood was still discussing constitutional amendments and parliamentary elections, and even after it called for Mubarak’s resignation, it participated in his second-in-command’s national dialogue.

Yet it is they who have gained the most, their political wing commanded a majority in the first parliamentary elections and despite the pledge not to field a candidate, Morsy contested and won presidential elections on the Ikwan’s behalf.